January 24th, 2012 — 5:30am

In my companies we make plans for each year’s growth, but honestly, most of the growth comes from new ideas we didn’t foresee in our planning.

We don’t have a bank of awesome but unused ideas to copy/paste into the annual plan. When we come up with a great idea, we try it right away. That means at any given time we’re out of great ideas, but not for long.

By being curious and paying attention, by building on top of the last improvement, by listening to our customers, we always come up with another improvement idea.

If you don’t have a list of “10 things that will change the game this year”, that’s probably ok. Wade on into what you’ve lined up so far, and keep your eyes open all the time for insight, inspiration, and opportunities to improve. It’s amazing how a year of continuous improvement adds up to a big leap forward.

January 20th, 2012 — 5:30am

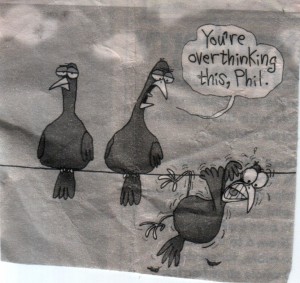

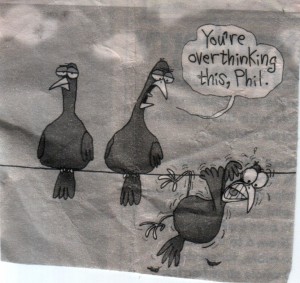

This cartoon is so me.

So much of what we fear can’t really hurt us.

January 19th, 2012 — 5:30am

The book “Confidence” by Rosabeth Moss Kanter is about winning streaks and losing streaks. The big idea of the book is that winning creates more winning, and losing creates more losing.

The reason? Winning creates optimistic expectations that more winning is possible. When players and coaches (or employees and managers) believe that more winning is possible, they work harder and take more initiative, and that creates more winning. Also, it’s easier to recruit great players and get support from investors when you’re winning, and hence more winning follows.

The same things happen in reverse with losing streaks.

One application: Don’t lose twice in a row.

Broader application: Create a culture of confidence where team members feel a shared sense of winning.

If you’re in a losing streak: Actions speak louder than words. Create visible evidence of a turnaround that your team can see and believe in.

January 18th, 2012 — 5:30am

When there’s change in a company, most employees think about it in terms of job security.

As an owner, I’m usually focused on the change itself and the exciting benefits I see for the future of the company. When I communicate I need to remember that employees may see it as a threat to their job security, even when I know there’s nothing to worry about.

As a manager, err on the side of sensitivity to job security concerns. And if possible, help employees see where job security truly comes from.

Job security comes from happy customers. If the customers aren’t happy, no company can provide job security. If the customers are very happy, the company will grow, and that increases job security.

Job security comes from individual performance. High performers should feel very secure in their jobs, and low performers should be very worried about their jobs.

No employee should be surprised to find out their job is in danger unless the company was surprised by an unforeseen event. And no high-performing employee in a high-performing company should live in fear of randomly losing their job. Employees deserve to know where they stand based on known and predictable factors. I think good managers provide that.

[It’s been pointed out to me that a lot of managers let people go for other, less-honorable reasons than those mentioned here. Unfortunately, that’s true. If you are a manager, you don’t have to be one of those. If you are a high-performing employee who works for one of those, I hope you feel empowered enough to look for a job at a healthier company.]

January 17th, 2012 — 5:30am

When you are creating something, like a business, an invention, or a screenplay, you don’t know the hourly rate you’re working for. It could be negative, it could be higher than any reasonable salary.

Monty didn’t know the hourly rate he was working for when he started creating MySQL in 1995. I guesstimate he spent at least 26,000 hours coding MySQL before he sold it to Sun thirteen years later. That’s over 3,000 work days filled with problem solving, fatigue, doubts, and no guarantees.

On top of that, Monty was giving MySQL away as free open-source software the whole time. He saw the long view. He wasn’t playing for a paycheck at the end of the week. He lived with the risk that events out of his control might mean the long view never even came true.

In 2008 he finally knew the hourly rate. His capital gains from the sale were roughly $26 million dollars. That’s $1,000 an hour. On top of that the software he created became a staple of the Internet software world, used by Facebook, Twitter, Google, WordPress (including this blog), and more.

If he had approached any software company in 1995 and said “I’d like you to pay me $1,000 an hour to write database software.” would any owner have agreed to that deal? No, he had to be his own owner, take a lot of risk, and show a lot of perseverance to make that deal come true.

When you don’t limit yourself to projects with a known hourly rate, you open up a big world of possibilities.