I spent a week at Silver Birch Ranch family camp this summer. Soon after arriving I observed examples of the extreme and uncommon level of service the staff and volunteers at this place always give to the campers. After a hot and tiring day of saddling and leading horses for trail rides, a volunteer was genuinely joyful about squeezing in one more pony ride for my little girl. We asked for some firewood, and the volunteer not only personally delivered it, but also built the fire and lit it for us! I saw dozens of examples of this extreme joyful service attitude, and not one example of reluctant or passionless accommodation.

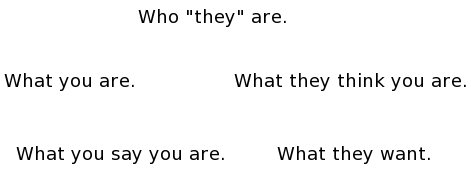

This level of service is a rare thing, and I was sure it didn’t happen by accident. I wanted to find out what created this culture of service.

Late one night after all the camp activities were closed for the day, I came across a group of high-school age volunteers on their free time. I shared my impression of their incredible service. I thought they’d say “Thanks, we work really hard to make it this way.” They didn’t. They said things like “It’s more fun being a volunteer than a camper.”, “We love working here.” and “We want you guys to have the best week possible.” They didn’t feel they were doing something difficult or unusual. This culture of service was in them at a deep level.

I was intrigued, but no closer to finding out what made the culture that way, so I asked “Are there volunteers who don’t fit in with this we-love-to-serve-you philosophy?” They said, yes, there are a few people that don’t get it, but they don’t last. The camp leadership will send people home who aren’t here to serve. In other conversations these were called “bad apples”. They didn’t think the extreme servants were unusual, they thought people interested in average-level service were bad apples. The culture had changed their perception of what’s normal.

As I pressed them to think about what created this culture, they repeated “This is what we want to do.” but added “They drill it into us too. They talk about it at every meeting.”

As the week continued I saw changes they had made since last year. Changes to take the level of service even higher. For example, at one meal this year the volunteers waited tables for the campers instead of serving us at the usual cafeteria line. As far as I could tell it was for no particular reason except to raise the level of service.

Later in the week I talked to the program director for that week’s camp. I asked him about the culture of service there, and he added two more causes to my list. “We lead by example. The leadership really lives it. When a new volunteer comes in here, they can see this is the way we all do things here.” And another reason, “We praise people who do this well. When I talk about service at our meeting tomorrow I’ll use your compliments as a success story.” I was starting to get the picture of how this culture came to be. But there was one more cause I didn’t see right away.

During the final breakfast of camp before we hit the road for home, I sat across from the president, the leader at the top of the organization. I didn’t see him eating. Based on what I’d learned about their culture, I’m pretty sure he was thinking about his first speech about service to a new group of volunteers starting that day. I didn’t want to interrupt his speech prep time, so I didn’t ask for his analysis. I just took a minute to compliment him on their success in building this culture of service. He didn’t say “Thanks. We’ve really achieved our goal with that .” He said “Sometimes we succeed, sometimes we fail. We always have to keep working on it.”

Looking at them from my “normal” culture, they had achieved a level of service so great, it would be a bit fanatical to try to raise the bar higher. To him, with their culture of service written in every molecule of his DNA, there was no time to rest, their were more places to improve, more people to induct, more opportunities to live it and repeat it and protect it.

I think now I understand how a company culture is built.